CPG Trends 10 June 2024

Ultra-processed food: What’s the debate and risks to health?

Global consumption of UPFs is expanding and with it the debate around the health implications of consumption. CPG companies should be aware of these key elements under discussion, to respond best to the uncertainty on the topic of UPFs.

Sevendots, Milan

5 minute read

There has been a resurgence of the debate around ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Global consumption of UPFs is expanding. UPFs now make up more than half the average diet in the UK and US, and a recent review of studies from 36 different countries found that ultra-processed food addiction is estimated to occur in 14% of adults and 12% of children. This leads to intense cravings, symptoms of withdrawal, less control over intake, and continued use, despite such consequences as obesity, binge eating disorder, poorer physical and mental health, and lower quality of life (1).

The challenge we face is that people rely on UPFs for a wide number of reasons including affordability and availability, and so removing them from our diets would require a huge change in the food supply system, which remains unachievable for most people. This potentially results in further guilt among those who rely on processed foods, promoting further inequalities in disadvantaged groups. (2)

The definition of Ultra Processed Foods

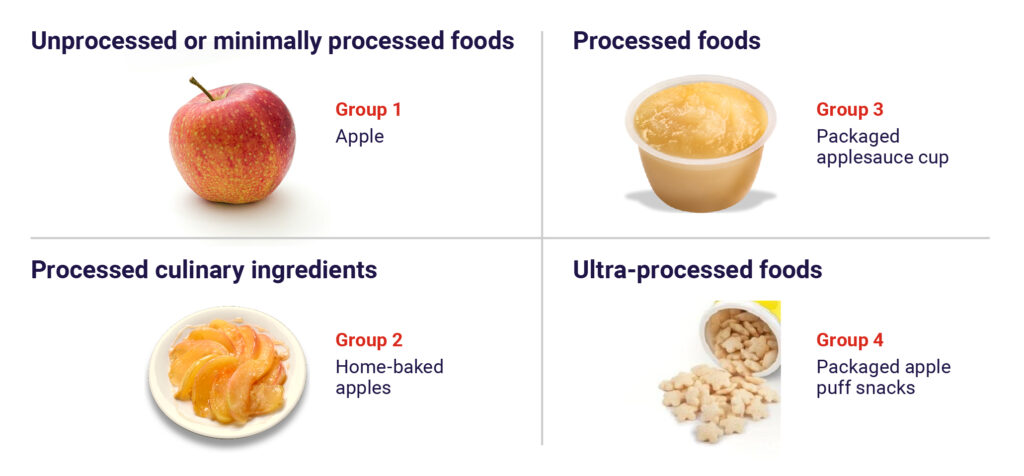

UPFs are defined as industrially manufactured products comprising deconstructed and modified food components which are recombined with a variety of additives (including emulsifiers, and other added ingredients) as part of food processing. The Nova classification, developed by researchers in Brazil more than a decade ago, groups foods according to how much they are processed. The levels within the classification system are defined as follows:

- Group one foods are minimally processed or unprocessed foods such as whole fresh fruit and vegetables, legumes, fresh meat and fish.

- Group two foods are processed culinary ingredients such as salt, sugar, and oils.

- Group three covers processed foods such as tinned fruit and vegetables.

- Group four are the ultra-processed foods: sweet and savoury snacks, ready meals, soft drinks, and other items that often have little if any intact food from group one. (3,4)

The mapping below provides a high-level summary of the food classification system:

What is the debate around UPFs?

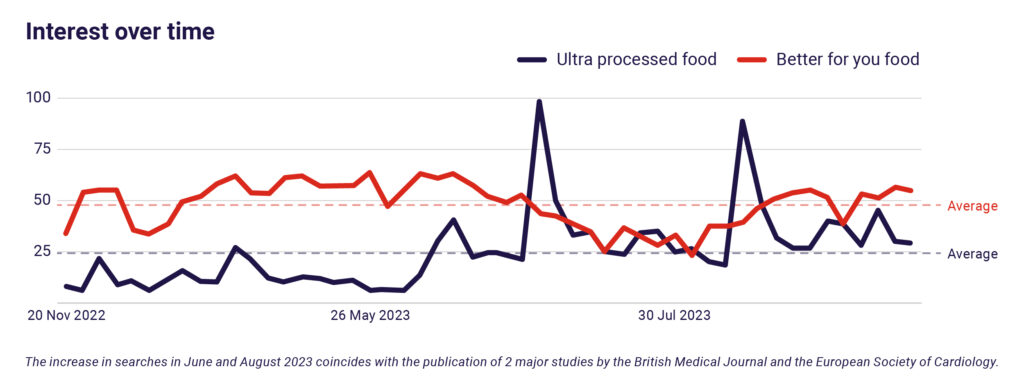

The classification is coming under question as being oversimplified, and the associated press coverage linked to the release of two major scientific studies in 2023 has raised the level of concern as well as confusion in the minds of consumers(5).

Several tensions are building up:

- Convenience vs. Health: Ultra-processed foods are often chosen for their convenience and long shelf life. The debate centers on whether the convenience of these foods justifies their potential negative impact on health. Advocates for healthier eating emphasize the importance of choosing whole, minimally processed foods.

- Marketing and Accessibility: Critics argue that aggressive marketing of ultra-processed foods, especially to children, contributes to unhealthy dietary habits. Additionally, the widespread availability and affordability of these foods may contribute to overconsumption.

- Global Health Concerns: The rise of ultra-processed foods is not limited to specific regions; it’s a global phenomenon. This has led to concerns about the potential impact on public health worldwide, especially in countries where traditional diets are being replaced by more processed and Westernized food choices. This drives the move back towards whole foods in favour of processed alternatives.

- Research and Scientific Evidence: Ongoing research into the health effects of ultra-processed foods continues to inform the debate. Some studies suggest correlations between high consumption of ultra-processed foods and negative health outcomes, but the scientific community is still exploring the causative factors.

The arguments for raising the level of alert

There is extensive data linking ultra-processed food with physical ill health, such as strokes, heart disease and heart attacks, as well as raised blood pressure. There is now evidence that consuming large amounts of ultra-processed food, especially drinks containing artificial sweeteners, is also associated with a higher risk of depression. (6) A study which tracked 10,000 women for 15 years, found that those with the highest proportion of UPF in their diet were 39% more likely to develop high blood pressure than those with the lowest. A subsequent study, involving a gold-standard meta-analysis of more than 325,000 men and women, showed those who ate the most UPF were 24% more likely to have cardiovascular events including heart attacks, strokes and angina. (7) The variety of negative health impacts because of overconsumption of UPFs is still being explored and therefore appears as a risk to consumers who are without all the information they may require when making choices at checkout.

However, UPFs still dominate shelf space, mind share and wallet share, and this needs to change.

The arguments for lowering the level of alert

The recommendation to avoid all ultra-processed foods may lead consumers to remove some nutritionally balanced foods from their diets as well. Some items that fall into the UPF bracket are foods such as whole meal bread, wholegrain breakfast cereals and yoghurts – all of which should be encouraged as part of a balanced diet. Processing technologies can also actually help to preserve nutrients and increase both safety and affordability of foods, while also reducing food loss and waste thanks to a longer shelf life.

The resulting uncertainty

As a result, Americans are split on whether all ultra-processed foods are bad for your health: 57% say yes, 43% say no. Overall, 74% would be willing to try an ultra-processed food if it included one of the following health benefits: better cardiovascular function; improved brain function; better sleep; better immunity; or increased energy. Additionally, 67% of adults would be willing to pay more for an ultra-processed food that contained more nutritious ingredients delivering better health benefits, regardless of household income. (8)

The confusion in the minds of consumers is not surprising given the fact that the industry hasn’t done a good job in the past: ultra processing has been often used to expand profits, extending shelf life by stripping out nutrients and reducing nutritional diversity and density, even though in reality processing can deliver unprecedented benefits such as providing fiber without compromising taste (9)

As a result, a recent US study (10) revealed that:

- 50% of consumers claimed to have heard of the term UPF, but were unable to explain what it means

- 30% claimed they were able to explain (but with a very broad range of definitions)

- 20% were not aware of the term

How should companies be responding?

There has been a shift around the definition of healthy foods as those produced using organic growing methods or non-GMO – which has been the case for decades – to defining healthy foods as those that are processed the least. Trying to swim against the tide is likely to be a losing battle. Damning scientific evidence that ultra-processed foods are a major contributor to weight gain, obesity and cardiovascular disease, amongst a variety of other health woes, has eroded consumer faith and trust in the packaged food companies behind them. Companies have a role to play in maximizing transparency when it comes to ingredient lists and processes in formulations, but also to support concerted efforts to help consumers make the right choices according to dietary guidelines at the grocery store.

The time has come to reinvent processed foods in terms of ingredient and sourcing choices and to provide much needed clarity to confused consumers who even suspect that all UPFs are not only unhealthy but are also bad for the environment due to the presence of chemicals and the hidden costs of industrial production – what 60% of European consumers seem to think (11).

The simplistic approach that the media is frequently adopting of classifying foods based only on the level of processing is running the risk of demonizing a broad range of foods as junk food, when many actually provide high levels of nutrients and contribute to a balanced diet.

The business case for creating healthier packaged foods, including healthier ultra-processed foods, is there. Those companies that take the lead will be the winners while those who will not adapt will find it increasingly hard to remain within the consideration set of consumers.

There happens to be another debate heating up at the moment around the positive or negative implications of AI. AI efforts could be directed to cracking the challenge of making healthier food more broadly accessible, irrespective of “the processing” that could become simply a red herring.